[urban interfaces] Blogs

Guest Contribution Jackson Moffatt – “In Touch But Not Together”: Exploring Urban Interfaces Through Electronic Dance Music Performance

The [urban interfaces] research group (ir)regularly accepts guest blog contributions. This contribution – written by Jackson Moffatt – is an edited version of a paper produced as part of the level 3 course at Utrecht University, called ‘Spaces and Screens’ in the BA Media and Culture; advanced trajectory Film & Media Culture and Comparative Media Studies. The course, co-ordinated by Lianne Toussaint, explores the relationship between screen technologies and cultural screen practices.

Jackson Moffatt is a third year Media and Culture student. Their research mainly revolves around New Media practices, specifically how performative and screened events can practically make use of emerging technologies. They are particularly concerned with the wider impact these new uses of media technologies can have on society.

“In Touch But Not Together”: Exploring Urban Interfaces Through Electronic Dance Music Performance

by Jackson Moffatt

Introduction

Created in London in 2011, The Boiler Room Project utilised web-streaming platforms such as YouTube to allow Internet spectators access to bedroom-mixes, streamed live by electronic music DJs to an exclusively online audience. By 2013, performances had migrated from the performing artists’ own space to public physical spaces. This was accompanied by an increase in not only the number of online spectators but also the addition of physically present spectators dancing around the performing DJ.

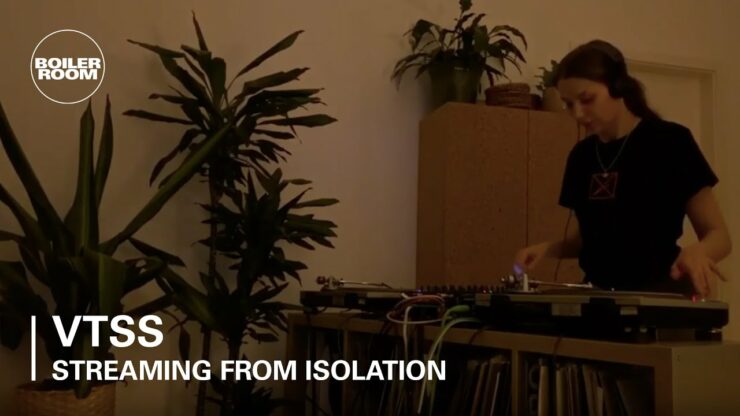

Fast forward to 2020 and restrictions put in place by the coronavirus lockdown led to the return of online-only streams, in an attempt to temporarily fill the void left by the closure of physical music venues. Boiler Room’s cultural acclaim and its historic contributions to the emergent model of online electronic music spectatorship strongly evidences its use for contributing to ongoing discussions on urban interfaces.

In this blog post, my use of the term urban interfaces — or interfacing — follows Michiel De Lange, Sigrid Merx, and Nanna Verhoeff’s usage in their collection of essays entitled Urban Interfaces: Between Object, Concept, and Cultural Practice. Urban interfacing as a practice and a theory is concerned with how “citizens, governments, and professionals shape urban environments.” (De Lange, Merx, Verhoeff 2019)

What I explore shortly hereafter with my two chosen case studies, on the other hand, is how urban interfacing as a practice helps to uncover how those urban environments can in return shape its citizens, governments, and professionals. Taking each instance of intersection between media, art, and performance within an urban space as a “specific instances and situations of making and relating with and within these spaces” opens up new understandings of our roles and capacities as potential agents of the urban interfacing process (De Lange, Merx, Verhoeff 2019). As a concept somewhat in its infancy, its academic and social relevance should not be understated, particularly considering the challenges presented to us in the past two years with relation to navigating our own familiar urban spaces.

Methodology and Case Study

I first observed two live-streamed electronic dance music performances accessed from the YouTube page of what is now referred to as just ‘Boiler Room’. Using a comparative dispositif analysis here helped to “discern what [was] specific to certain screens and specific uses or practices” (Verhoeff and Van Es 2020, 4). Here, it becomes evident how the urban interfacing of media, art, and performance taking place in public city space is subject to being shaped by, and so too shaping, its occupants. The first performance is from Polish DJ VTSS, performing at a physical Boiler Room event in London, and streamed live on YouTube simultaneously in March 2019 pre-lockdown. The second comes from the same artist, however, instead streamed from isolation inside their home a little over one year later in April 2020 during the global lockdown.

Through these two cases, as well as Nanna Verhoeff and Sigrid Merx’s work on post-lockdown scenographic figurations, I further develop Verhoeff’s concept of spacecificity, and Adriana de Silva e Souza’s notion of hybrid space (Silva e Souza 2006) (Verhoeff and Merx 2021). My aim is to highlight how different media can shape our experience of the public and private depending on the individual experience of screen space and screen temporality. In its updated form, this idea of hybrid spaces takes on a dual meaning, no longer referring exclusively to a mix of the virtual and the physical. Instead the term suggests a newfound hybridity between scenographic (theatrical or performative) configurations of the urban and public, and the domestic and private.

By considering the dispositif of the two chosen performances, more definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the frictional dynamics of the urban transformation that have emerged during the course of the coronavirus pandemic. I also argue that this new understanding of hybrid space is best thought of as a spectrum or scale. Both the Boiler Room London performance and Boiler Room isolation performance are examples of hybrid spaces, however, the degree to which this hybridity is experienced is complex and based on a variety of technological, contextual, institutional, and other historical influences (Kessler 2007).

Re-thinking Spatial Hybridity

The idea of hybrid space was originally based on the belief that virtual communities would grow out of real-world communities who were increasingly migrating to cyberspace. The pre-lockdown Boiler Room London screening situation evidences this idea of natural migration to online space, as spectators could choose to be physically co-present, or co-present in terms of simultaneous live-viewing. On the other hand, the performance streamed from isolation suggests a forced deportation of the spectator to the virtual, rather than the migrative process that took place in Boiler Room’s pre-lockdown forms.

If hybrid space is understood to be one in which Users (plural) are connected in realtime to other Users via digital technology depending on their relative positions in physical space, then what happens when these Users – in this case spectators of VTSS – are all in the same relative position behind their own screen? No longer are the dancers swarming the DJ booth, instead the performer stands alone, truly isolated. By revoking the physical presence of every User besides VTSS, it reinforces the post-lockdown urban scenographies discussed by Verhoeff and Merx. In this instance however, the urban interfaces are no longer solely urban, and instead become domestic or privatised scenographies that have been influenced by wider social circumstances of post-lockdown urban configurations.

Brigette Biehl has argued DJing — a type of media performance — can be viewed as a co-creative performative art form in which feedback loops are generated by an interaction between the text-screen-spectator (DJ-equipment-dancers) (Biehl 2018). In the pre-lockdown Boiler Room performance, the DJ and physically present dancers enjoyed an affective relationship in which VTSS responds to the crowd by changing their play style, tempo, and more. When the audience is relegated — or isolated — to an online space, the fundamental composition of a screening situation as a whole shifts. It becomes clear that what may have originally been defined as solely a spectator, if only analysing the dispositif of the streamed performance, is arguably part of the wider text itself. Without the dancers to respond to, the DJ’s performance becomes more insular.

Whilst a theatre performance often invokes audiences reactions that are internalised or imagined, spatially co-present DJ performances invite bodily responses which can “be perceived visually, acoustically, and sensually and strongly influence the overall atmosphere” (Fischer-Lichte 2004, 36). Comparing the dispositifs of Boiler Room London and Boiler Room from isolation then, it becomes clear that the removal of spatially co-present spectators/dancers alongside the DJ means participants watching the isolated performance more closely resemble theatre-goers. They lose the power to influence others via the collective interaction consistently recognised within dance and performance studies.

The ‘Spacecificity’ of the Dispositif

Navigating screen space involves the continuous construction of space through screens, in a way that infuses physical space with material architecture (Verhoeff 2012, 128-129). This is what we see in the case of Boiler Room London, as the screening situation (material architecture) on YouTube merges with the physical space of London. This phenomenon is known as the spacecificity of the dispositif: “the way the spacing of screens and spectators is performative in that it creates an experience of this spatial relationship” (Verhoeff 2012, 131).

In framings of hybridity such as the two chosen performances, the aspect of connectivity is central to achieving a hybrid spatial experience (Verhoeff 2012, 126). This connectivity, particularly within the sense of a mobilised screening situation such as the isolation performance, “[negotiates] a certain sense of the relationship between public and private” (Verhoeff 2012, 126). This influences how spectators experience a situation differently from space to space, and time to time. Spectators within hybrid screening situations such as Boiler Room London and Boiler Room SFI are bound together in a way that questions existing frictions between the private and public. This furthers the need to view such screening practices via a spectrum in which all complexities are fully considered.

What becomes clear then when analysing the dispositif of Boiler Room SFI in comparison to that of Boiler Room London, is the way in which the screening situation forced by the complexities of the post-lockdown urban environment, have dismantled the autonomous and co-creative mobile and hybrid space that Boiler Room London – and any pre-lockdown Boiler Room events – had so delicately achieved. This reinforces the somewhat paradoxical experience discussed by Verhoeff. One in which any spectators relegated to an exclusively online screening situation are “in touch, but not together” (Verhoeff 2012, 126).

Conclusion

The idea of hybrid space alongside Brigette Biehl’s analysis of DJ-spectator co-creativity proved useful for evidencing Frank Kessler’s argument. Mainly, that the concept of the dispositif should be seen above all as a way in which to “account for the complexities of media (texts) in situational contexts offering, or aiming at producing specific spectatorial positions” (Kessler 2007). Nanna Verhoeff and Sigrid Merx’s work on post-lockdown urban figurations assisted in further clarifying the dual nature of hybrid space. Now the term infers a hybridisation between the scenographic figurations of the urban/public and the domestic/private.

Thoughts on mobile spaces and programmed hybridity helped to strengthen the claims that hybridity should be viewed on a spectrum, and not as binary oppositions, due to the complexity surrounding any potential object of analysis. Verhoff’s work on the idea of ‘spaceficity’ was implemented in order to ascertain how the relationship between spectator, screen, and text are impacted by the way space and time are configured within a public or urban screening situation (Verhoeff and Van Es 2020, 5).

These specific spaces are the mobile screening situations that audiences conform to in order to still experience the screening situation in whatever way possible. The lack of control over these specific spaces on behalf of those constructing the performance (the DJ, the venue, etc.) however, means that something – although exactly what is unavoidably subjective – is lost between VTSS performing from London in 2019, and from isolation in 2020. Here, urban interfacing as a practice and a theory, gives greater clarity as to how media, art, and performance can negotiate the tensions within public space, particularly in such emotionally charged times.

Bibliography

Biehl, Brigitte. 2018. “‘In the mix’: Relational leadership explored through an analysis of techno DJs and dancers.” Leadership 15, no. 3: 339-359.

Boiler Room. 2019. “VTSS | Boiler Room London: Warehouse Party.” Streamed March 2019 at Boiler Room Warehouse Party, London. Video, 59:49. www.youtube.com/watch? v=D6sUo7Bw3Tc&ab_channel=BoilerRoom.

Boiler Room. 2020. “VTSS | Boiler Room: Streaming From Isolation.” Streamed April 2020 at VTSS’s home. Video, 1:27:53. www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZlIXogjQ8X0&ab_channel=BoilerRoom.

De Lange, Michiel, Sigrid Merx, and Nanna Verhoeff. “Urban Interfaces: Between Object, Concept, and Cultural Practice.” Introduction to Urban Interfaces: Media, Art and Performance in Public Spaces, edited by Verhoeff, Nanna, Sigrid Merx, and Michiel de Lange. Leonardo Electronic Almanac 22, no. 4 (March 15, 2019).

De Souza e Silva, Adriana. 2006. “Mobile Technologies as Interfaces of Hybrid Spaces” Space and Culture 9, no. 3: 261-278.

Fischer-Lichte, E. 2004. “Die Wiederverzauberung der Welt. Eine Nachbemerkung zum Begriff des postdramatischen Theaters.” In: Primavesi, P, Schmitt, OA, edited by AufBrüche. Theaterarbeit zwischen Text und Situation. Berlin: Theater der Zeit, 36–44.

Kessler, Frank. 2007. “Notes on Dispositif.” Accessed June 18th 2021. http://www.frankkessler.nl/ wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Dispositif-Notes.pdf.

Verhoeff, Nanna. 2012. “Programming Hybridity.” In Mobile Screens: The Visual Regime of Navigation. 124-129. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Verhoeff, Nanna and Karin van Es, “Dispositif Analysis: How to Do a Concept-Driven Dispositif Analysis.” Third edition. Utrecht: Utrecht University. 2020.

Verhoeff, Nanna and Sigrid Merx. 2020. “Mobilizing Inter-Mediacies: Reflections on Urban Scenographies in (Post-)Lockdown Cities.” Mediapolis: A Journal of Cities and Culture 5, no. 3: 15.