[urban interfaces] Blogs

Why Your Well-Intended “Zero-Waste” Tips Don’t Do It for Me

Written by Hymke Theunissen

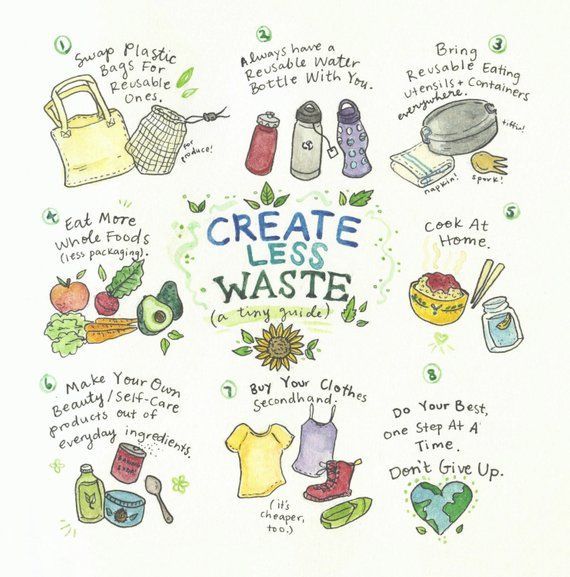

A hand drawn guide pops up on my Instagram. Quickly scribbled and colourful reusable items are surrounded by little green leaves. A bottle, a bag and some second-hand clothes circle around the text “CREATE LESS WASTE.” The guide looks simple. The items seem to carelessly dance in a happy green environment.

Through social media we can share our lives, and our view of the world. We can motivate others to relate to the environment in a certain way. I saw this picture, capturing a certain worldview, and instead of feeling hopeful for the future, I felt annoyed. How can I be displeased when looking at such a joyful picture?

Before I elaborate on my feelings, we first need to understand the post. This guide provides a certain view of the future. In the words of Sheila Jasanoff, it shows a sociotechnical imaginary. These imaginaries are “collectively held and performed visions of desirable futures” (Jasanoff 2015, 19). It describes the ideas people have about what they want the future to be, and the actions that they take towards this. Technology plays a dominant role in these imaginaries. The person who made the effort of sharing this picture on Instagram expresses what they imagine the future could be, since the actions we undertake in daily life are themselves performances of existing imaginaries. What we currently do, or don’t do, reflects what we want our future to be.

Back to my annoyance. Is this feeling occurring simply because someone is correcting my behaviour? Someone is telling me how to live my life? No, that can’t be it. I agree with the actions that are proposed in this guide. I understand that measurements need to be taken to prevent the resources of the earth from being drained at such high speed as is currently happening. I want to live a more sustainable life, and I own most of the items in this picture. I always bring my own bag when shopping, I drink from a reusable water bottle and bring my sandwiches in a lunch box. Moreover, I think a sustainable future is achievable. I see people around me taking action and I notice how this effects the options that are available for consumers. The vegan options on menus are expanding because we express our desire of eating less meat and more plant-based food.

Basically, as far as sociotechnical imaginaries go, my sustainable actions express the same values as the person sharing this guide. But still, I felt displeased.

Then I realised my annoyance was not directed towards the guide or the person sharing it, but it had to do with the limited framework that this guide proposes. Maybe the picture emphasises my powerless feelings in the situation of limiting my waste. Maybe the focus on re-using and restricting your impact on this world makes me feel like I can never do enough. There is a limit in limiting yourself.

Maybe it goes against my wishes to create something.

I was introduced to the book Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth (2017). One sentence from this book spoke to me. Raworth describes how zero-waste is an odd strategy. If a factory can produce as much clean water as it uses, why should it not produce more? “Why simply take nothing when you can also give something?” (Raworth 2017). Such a simple thought. Why hadn’t I realized this before?

I am annoyed because the guide wants me to stop taking from the earth, instead of giving back more. The person sharing this guide is reminding me of the restrictions of a “zero-waste” strategy. The picture expresses a view in which the focus lies on repairing. We have already taken too much from the earth, and now we need to repair the damage we have done by taking much less. Instead of only focussing on making your food at home, we could also see possibilities in what to do with the leftovers.

While one could question whether there are any practical solutions that Raworth (2017) proposes in her book, or that it merely indicates an abstract way of perceiving economical models, her sentiment of ‘generating’ provides a valuable framework. If we were to design our lives not from the viewpoint of limiting our damage, but generating something valuable, this would provide room for creative solutions that focus on building a future.

So, when we use Instagram as a medium to motivate other people to express a certain sociotechnical imaginary, let’s focus on how we can use our creativity. Don’t limit yourself in repairing, but think of new ways to generate something. My annoyance will soon fade if I stop thinking of how I should limit myself, but rather see possibilities where I can give back more.

References

Jasanoff, Sheila. 2015. “Future Imperfect: Science, Technology, and the Imaginations of Modernity.” In Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, edited by Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim, 1-33. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Raworth, Kate. 2017. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-century Economist. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

This article is part of the graduate seminar series Urban Ecologies 2020.