[urban interfaces] Blogs

Rethinking the Traditional Moldovan Carpet as a Medium of Symbiosis between Human, Nonhuman and Culture

Written by Nicoleta Cîrlig

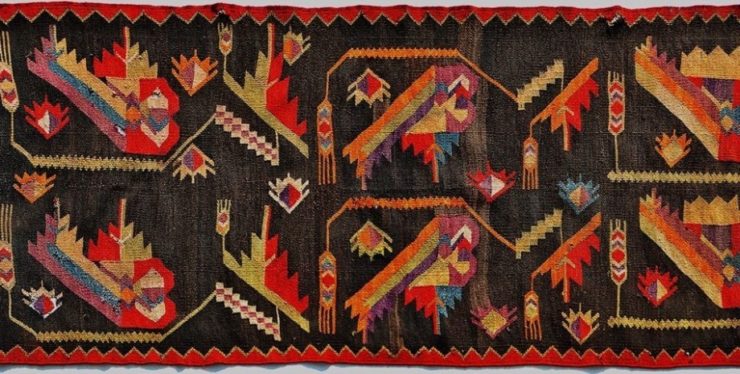

Moldovan Traditional Carpet. Source: Diez.md.

Deborah Lupton describes animism as a term used in sociocultural theory to refer to the attribution of life, human characteristics or spirituality to phenomena that are otherwise culturally considered non-living or nonhuman. It is a relational perspective that views humans and nonhumans as interconnected and trans-agential (Lupton 2019). At the same time, animism derives from affective forces, from the power that objects have to create dramatic effects, or a flow of energy between and with the components of assemblages, as Lupton points out. How does then the Moldovan traditional carpet embody this concept and how does it embody a collaboration between nature, human and culture?

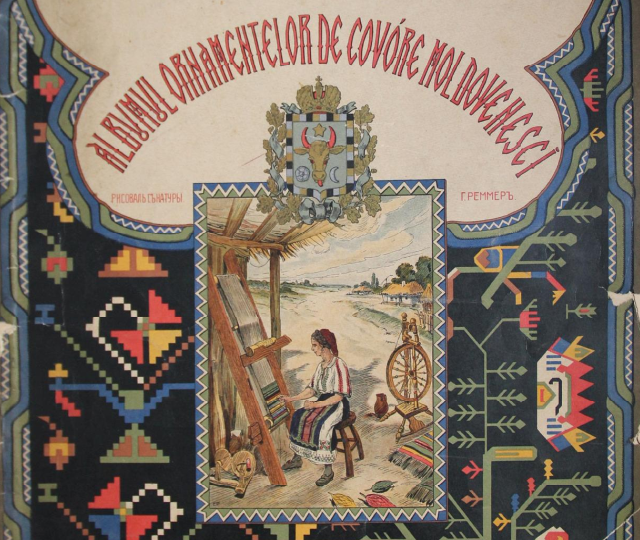

It is very hard to define or describe the Moldovan traditional carpet. Especially because of its diversity and variety from region to region and from one historical period to the other. Created to be an ornamental piece, in its original form this cultural object was meant to be placed on walls to be admired, read as a book, transmit history and become the centerpiece of cultural heritage in every household. Depending on the purpose of the carpet, the vast majority of the motifs represent nature like the tree of life, vine, water droplets, flowers, rivers. The process of creating such an object encompasses the use of specific materials like natural wool, plant based dye and special frames created out of wood and string on which the ornament was woven.

Weaving frame illustration from 1912. Source: Albumul ornamentelor de covoare 1812 -1912.

Originally, the carpets were created by women who were responsible not only for the manual labor, but for laying out the correct ornament which would then communicate an intended message. They had the task of weaving history and culture and transmit it to the next generation. In the majority of cases, the carpets’ ornaments emphasize our people’s unity with nature, our bond with our land and the importance of preserving a collaborative relationship between humans and natural elements. It was considered an almost living, full of wisdom entity, the soul and spirit of the household. [1] The carpet, thus, stands as a testament of female labor and connection to nature, and understanding all the forces that had to come together to create an artwork like this acts as critical exercise. An exercise of seeing beyond the tapestry and understanding what the details tell us about our relationship with plants, animals, the land. Integrating them in the current reality and asking ourselves: “How do the symbols resonate with us now?”; “How can we use them to ask for a more response-able bond with the nonhuman?” As Donna Haraway puts it “The details link actual beings to actual response-abilities” (2016). Response-abilities towards how we see nature and what do we use it for, the link of female labor with culture and the power (or the burden) to create it.

As we attempt to get closer to our roots and keep our culture alive, the Moldovan traditional carpet and its enchantment is being revived, as it has become a subject of various exhibitions in the Natural history museum and in the Ethnography museum in Moldova. Its ornaments are used on various artworks, visual representations, light shows. The carpets most abundant in symbols still hold a special place in every rural Moldovan household, being treated as an almost spiritual entity. It acts as an affectual artifact that brings you closer to your ancestors embodying soul, tradition and the bond between people and nature. A symbiosis between human and nonhuman, the map of the land and its spiritual values. At the same time, although not acknowledged yet, it acts as testament of the cultural labor carried by women through the centuries.

I would like to rethink this art piece then as a mobile medium that holds the power and the aura to create new meanings for reconstructing our relationship with nature and understanding the contribution of female labor in producing and transmitting culture. This staple piece of our history makes me feel a sense of being in touch with my ancestors. I see in it the spirit of my culture, my roots, the labor of the women who created it. I feel pride, solidarity and unity with them and I think – why wouldn’t we repurpose its aesthetic values, liberate it from the confinements of the museum and set it free to retell us our story of unity with our surroundings?

Notes

1. In her paper “Moldovan carpets – pearls of ethnic heritage, on the verge of endangerment carpets,” the moldovan ethnologist and researcher Elena Postolachi-Iarovoi mentions that a traditional carpet in the household would caress the soul of the family, it would warm up the house creating a beautiful and aesthetically pleasing space which would in turn show the spirituality of the people living there. She says: “There is a communication process that takes place at home between people and objects, which creates a certain state of the spirit which depends on the person liking the object or not.” In original: “Acasă, are loc un proces de comunicare a omului cu obiectele, care îi creează o anumită dispoziţie în funcţie dacă ele îi plac sau nu” (Postolachi-Iarovoi 2009).

References

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthuluscene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lupton, Deborah. 2019. Data Selves: More-Than-Human Perspectives. Polity Press.

Postolachi-Iarovoi, Elena. 2009. Covoarele moldovenești – perle din zestrea etnică, astăzi țin calea spre dispatiție. Akademos.

This article is part of the graduate seminar series Urban Ecologies 2020.